Coral reef evolution notes¶

Section intro

In this chapter, we will discuss the dynamics of coral reefs with a focus on their long term evolution. We will see different types of modelling approaches that focus on long-term (century to millennial scale) and large-scale (regional to continental) evolution.

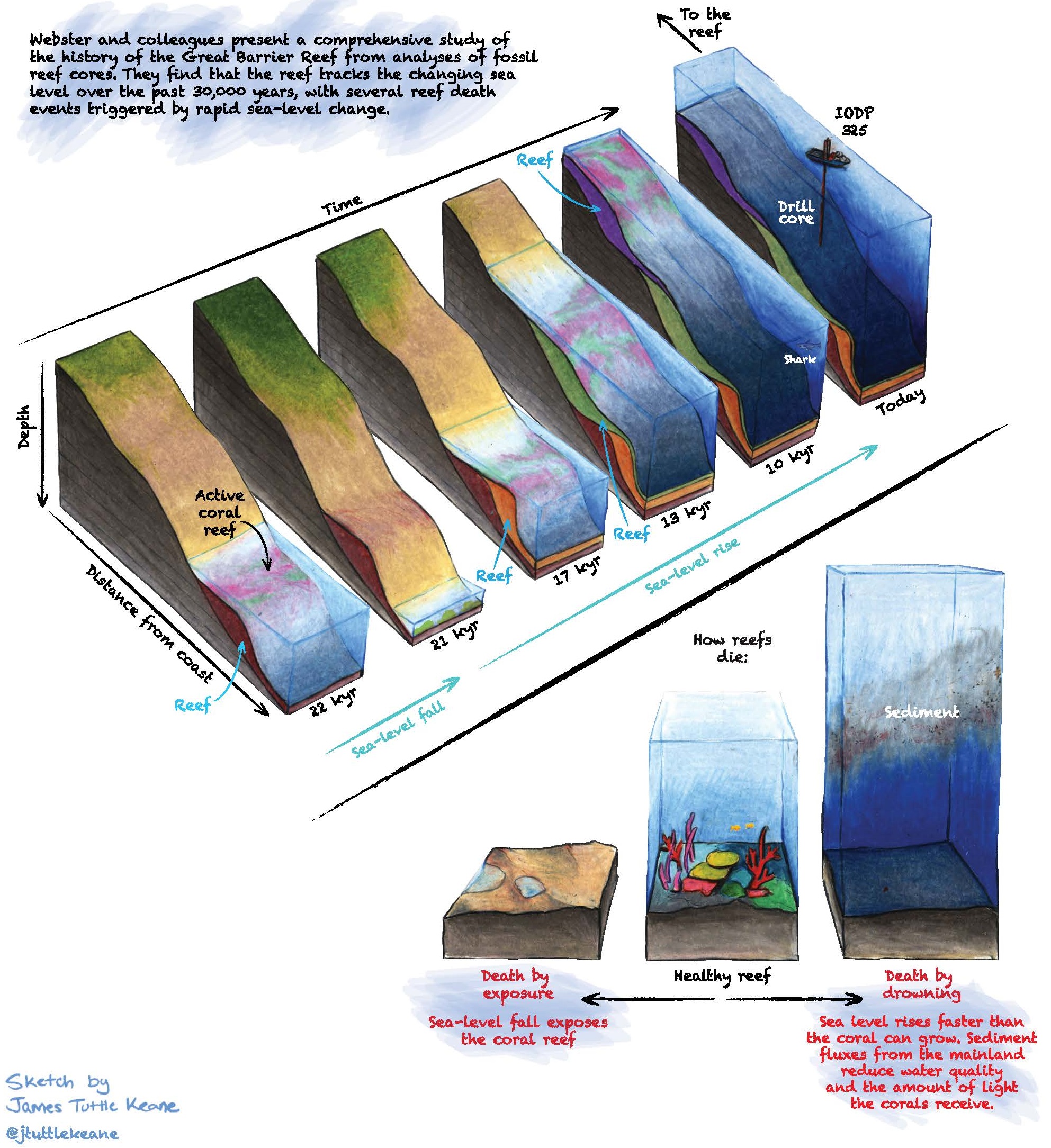

Case study: The Great Barrier Reef¶

The Great Barrier Reef is the largest living organism on the planet, stretching over 2,600 kilometres in length and covering 344,400 km2 of the ocean. It consists of 2,900 individual reefs and 900 islands.

The growth and evolution of the reef did not happen overnight. In fact, it is over 20 million years in the making. The reef as we know it today is built on the backs and bones of many millions of years of coral as the ocean levels have changed, islands have formed and land has settled.

Note

The GBR that we know is about 6,000 to 8,000 years old and sits on the platform of a much older reef. The formation, location and depth have changed as the continental shelf and sea level have changed and will likely continue to do as sea levels change and the earth’s crust shifts.

Amongst the approaches available to study coral reef platform formation, Stratigraphic Forward Modelling (SFM) has become a powerful tool. SFM simulates processes acting over geologic timescales and consists in iteratively refining parameters to improve the match between observed and predicted morphologies and stratigraphies. Through this iterative procedure, it helps to evaluate and quantify parameters that cannot be observed directly such as sedimentation or carbonate production rates. In that sense, SFMs address the short-comings of qualitative investigation techniques applied to carbonate systems.

Main physical forces acting on carbonate platform¶

Corals are calcium-carbonate-secreting, and their ability to grow and build reef structures is dependent upon favourable environmental conditions. Environmental factors affecting growth have been classified by Veron (1995) as latitude-correlated factors, and those that are regional or local in character.

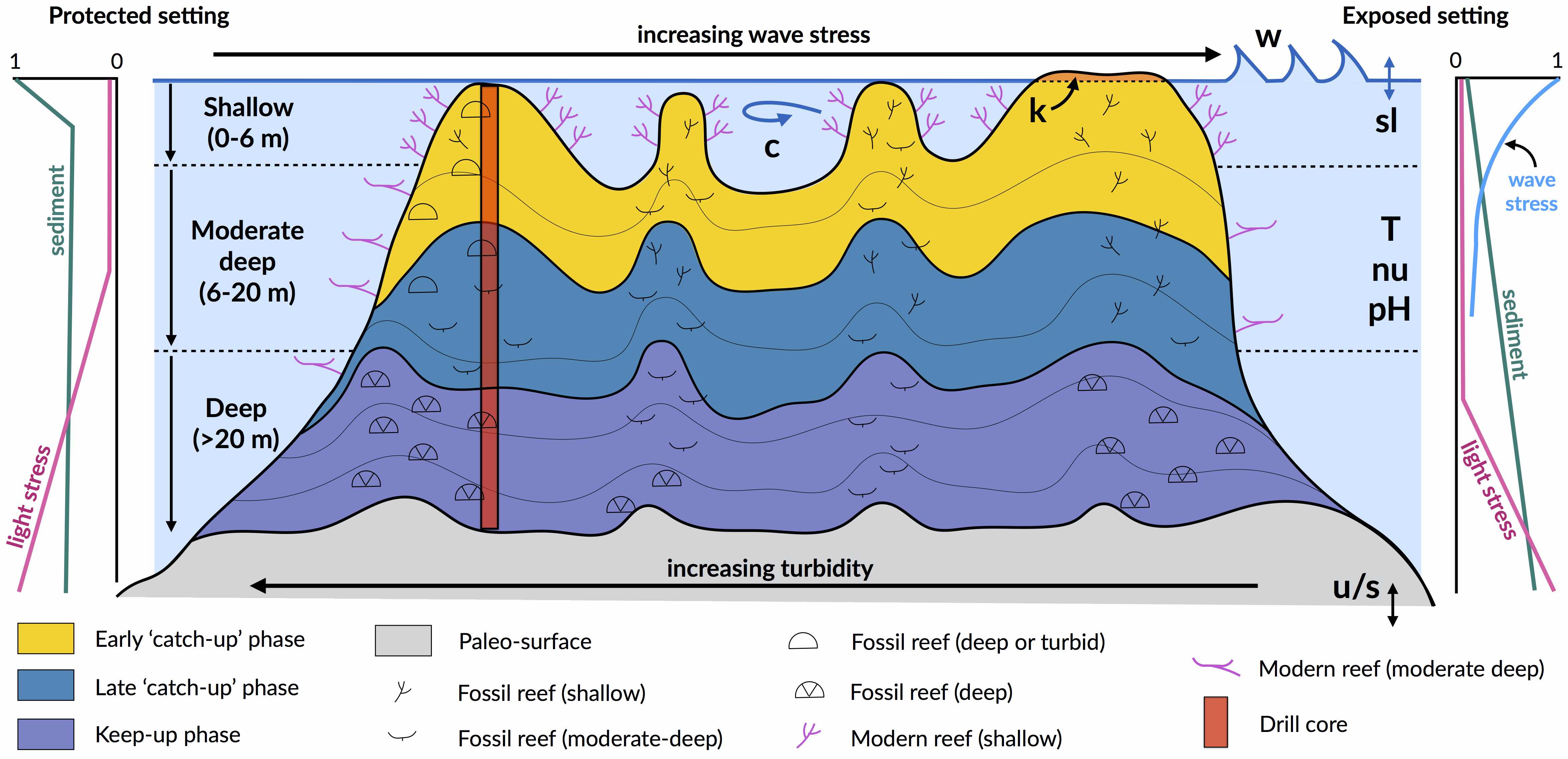

Fig. 27 Schematic figure of a hypothetical reef with transitions from shallow to deep assemblages occurring down-core, illustrating growth-form responses of corals to environmental forcing including light, sea level changes (sl), hydrodynamic energy (w wave conditions and c currents), tectonic (u uplift and s subsidence), oceanic conditions (T temperature, nu nutrients, pH acidity), karstification (k) and sediment flux.¶

Latitude-correlated factors include sea surface temperatures (SSTs), solar radiation and water chemistry. These factors are likely to be affected most by climate change, potentially shifting the optimal environmental suitability for coral calcification toward the poles.

Regional and local environmental factors include wave climate, salinity, water clarity, nutrient influx, sedimentation regime and depth/composition of the initial substrate. These factors affect coral species to different extents, controlling the distribution of coral communities across a reef. Over longer time scales, they also shape the rate of calcium-carbonate production, framework building by corals, and the accumulation of sedimentary deposits.

Note

Despite the significant, short-term impacts cyclonic storms and terrigenous sediment input have on reef systems, pulse disturbances are smoothed out on geologic scales where reef systems are characterised by remarkable persistence and resilience. The slow and persistent factors (e.g., sedimentation, wave climate and accommodation) are those that exert a stronger effect on the distribution of coralgal communities across a reef.

Accommodation¶

Accommodation is the vertical and lateral space in the water column above the substrate within which corals can grow. The effect of accommodation on coral growth is the most well-understood constraint on the waxing and waning of reef growth, governed by the rate of vertical accretion of reefs, sea-level rise, subsidence and uplift.

Accommodation affects coral growth in two ways:

Firstly, light attenuates with depth in the ocean, and as corals are photosynthetic organisms, carbonate production decreases with increasing water depth.

Secondly, wave energy and water flow also decreases with depth, such that corals growing with reduced accommodation (i.e., in shallow depth) experience increased hydrodynamic energy.

Important

The effect of light is assumed to dominate over the effect of water movement in limiting carbonate production, however both effects play a role in determining coral composition and, in turn, rates of vertical accretion.

Generally, assemblages within 20 m depth have the highest accretion rates (10-20 m/kyr) than those deeper (< 10 m/kyr). Holocene reef growth largely occurred due to initially rapid sea-level rise (∼10-6 ka), which created new accommodation and favourable conditions for reef ‘turn-on’ on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR). Some reefs were able to keep pace with sea level rise (‘keep-up’ reefs), while others caught up after sea level stabilised (‘catch-up’ reefs), and others drowned (‘give-up’ reefs).

Examples of reef architecture evolution modelling

The 2 movies above are based on a numerical model of reef architecture evolution proposed Husson et al. (2018) and illustrate the response of reef productivity to the changing pace of sea level oscillations during Pleistocene under different tectonic settings.

Hydrodynamic energy¶

At the organism level, currents, water flow and oscillatory motion induced by waves are critical in modulating physiological processes in coral and thus influencing coral growth rates.

High water flow increases rates of photosynthesis by symbiotic algae, nutrient uptake by corals, particle capture and facilitates sediment removal from coral surfaces, all of which contribute to enhanced primary production.

At the extremes, too little flow can be lethal in corals by inducing anaerobiosis, whereas extreme wave events cause mechanical destruction and can lead to long-term changes in community diversity and structure.

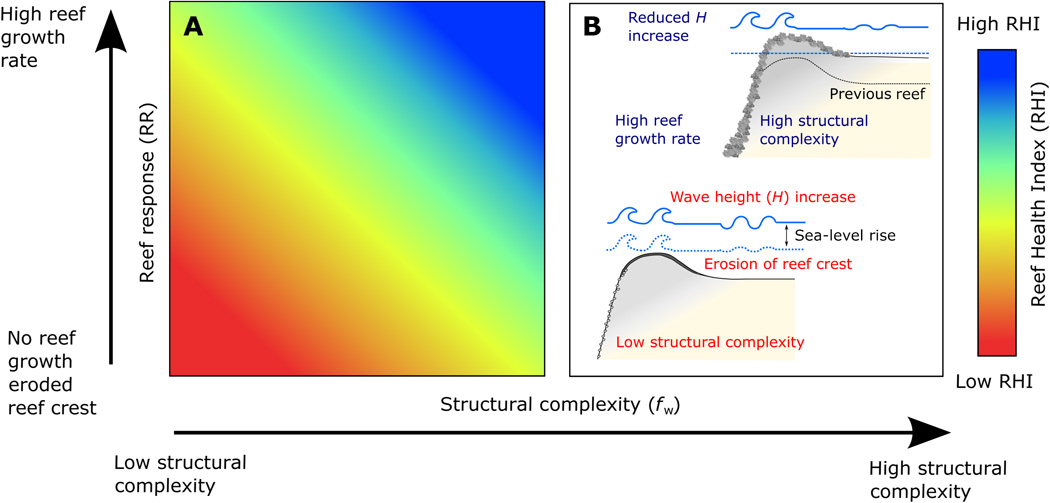

Fig. 28 Coral reef structural complexity provides important coastal protection from waves under rising sea levels (from Harris et al. 2018).¶

Note

Waves exert a strong spatial control on hydrodynamics of reef systems. Wave energy is dissipated on shallow reefs from bottom friction and wave breaking, with the former effect dominating the latter on reefs with high surface rugosity of coral communities (Harris et al. 2018). Furthermore the geomorphology and high-rugosity of reefs cause wave refraction, such that wave energy is highest on the ocean-facing margin (exposed setting) and lower in back reef (protected setting) lagoonal and marginal environments that are protected from the prevailing winds and wave energy. As a result, wave-induced bottom stress strongly influences coral cover and community composition.

While overall, corals tend to grow more rapidly in higher-flow environments, high wave energy also has a depressive effect on reef growth in shallow (<6 m) environments. Field studies demonstrate that coral communities form where species that are capable of thriving in particular hydrodynamic conditions grow together and adopt forms suitable to those conditions. Hence, wave-induced bottom stress affects community organisation spatially, with a clear zonation pattern from the reef crest to the reef slopes.

Sediment input¶

Important

High fluxes of both terrigenous and autochthonous sediments are widely identified to have both direct and indirect inhibitory effects on coral reef growth.

Firstly, elevated turbidity attenuates ambient photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), which inhibits the ability of corals to meet energy requirements through photosynthesis. Secondly, smothering and abrasion by sediment blankets can impair feeding and cause physical damage and direct mortality.

While the lethality of sediment exposure is determined by the intensity and duration to exposure, generally the long-lasting impact of turbidity regimes is known to depress coral growth and survival. For instance, elevated turbidity on mid-outer platform reefs caused by the suspension of sediment on the Pleistocene GBR reef substrate during initial flooding ∼9 ka is hypothesised to be responsible for a delayed initiation of coralgal growth.

Autochthonous carbonate gravels and sediments (i.e. aragonite, calcite and high-magnesium calcite), produced by the growth and mechanical destruction of reef organisms through physical, biochemical and bio-erosive processes, are important determinants of the spatial and temporal distribution of coralgal communities on long timescales.

Prevailing wave and current conditions of even moderate energy resuspended fine-grained carbonate sediments are key in generating stable turbidity regimes on reef systems, particularly in lagoons, on leeward rims and on reef slopes at moderate depths due to the decreasing water energy gradient both laterally and with depth. Similarly, prevailing turbid conditions are less common at shallow sites, especially on the windward rim due to wave-driven sediment removal.

Note

The spatial variation of suspended sediment loads is a critical environmental factor influencing coral community distribution across the reef and with depth. Turbid conditions are inimical to certain communities such as shallow-water corals, yet some species and communities are tolerant of elevated turbidity conditions on leeward rims or species that thrive on reef slopes at depth. Hence, the spatial variation in turbidity is reflected in coral community distribution both across the reef and with depth.

Coral reef modelling approaches¶

The organisation of coral reef systems is known to be large and complex and we are still limited in our understanding of their temporal and spatial evolution.

Additionally, most datasets of carbonate systems are often linguistic, context-dependent, and based on measurements with large uncertainties. Alternative modelling approaches, such as fuzzy logic or cellular automata algorithms, have proven to be viable options to simulate these types of system.

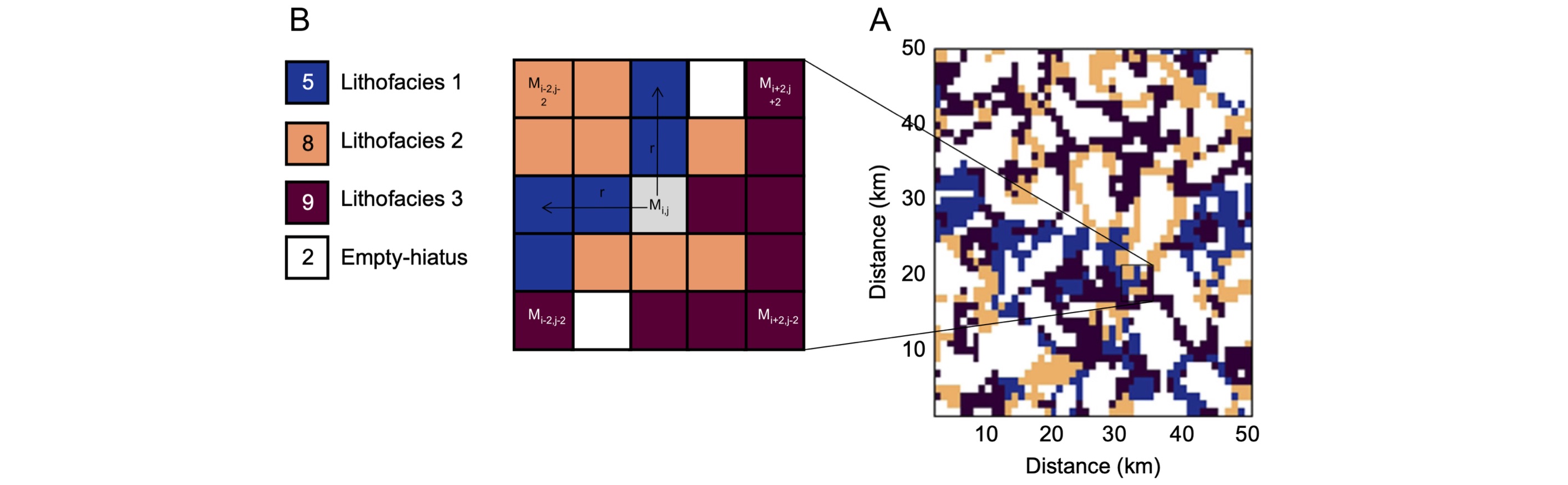

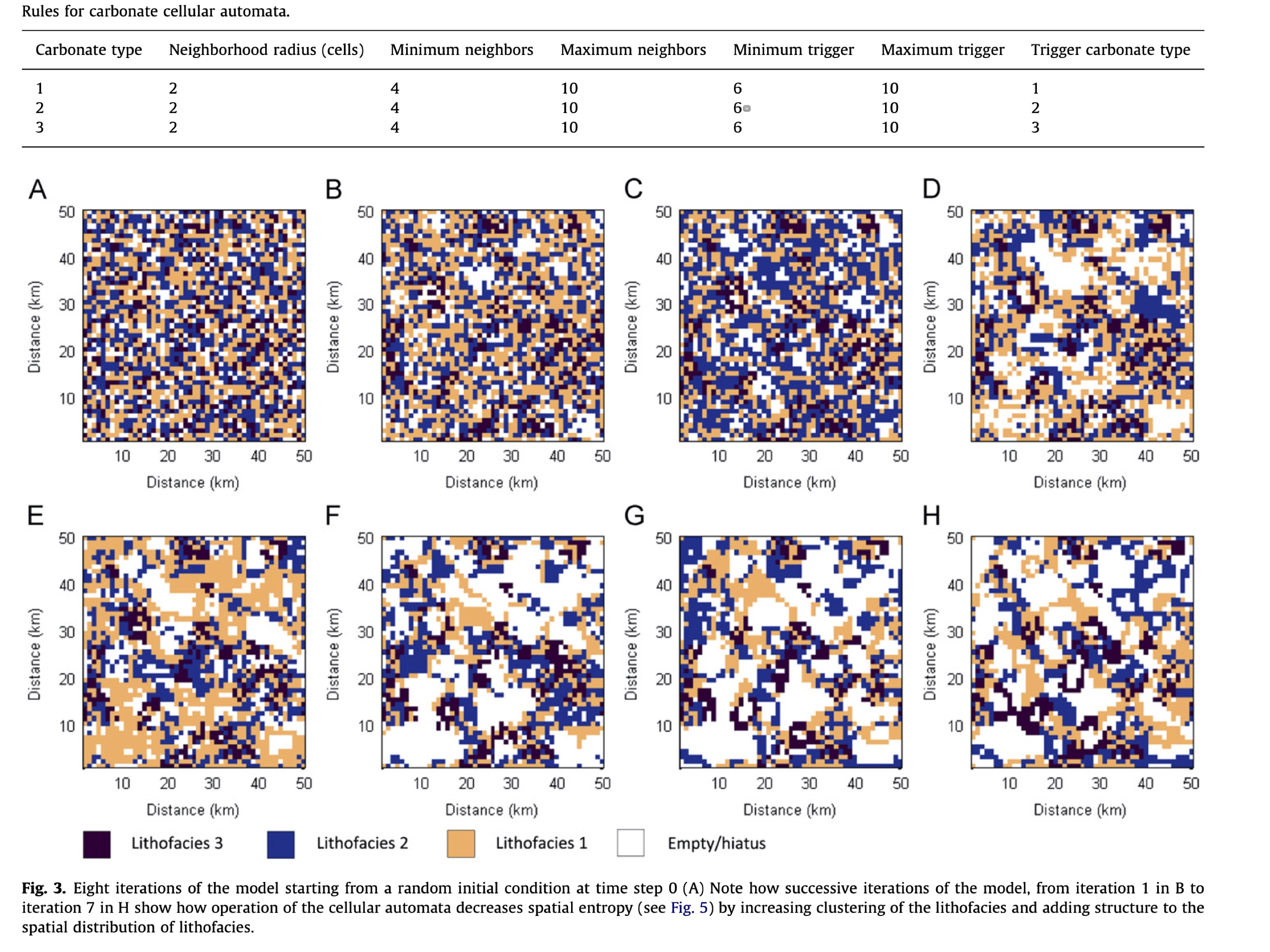

Cellular Automata¶

Cellular Automata (CA) are a type of discrete numerical model that have been used to simulate carbonate platform development. They can be entirely deterministic in their calculation, generate relatively complicated results from relatively simple rule-based computational algorithms, and are at least loosely related to biological concepts of space, competition, and population dynamics.

CA are composed of a regular grid of cells, each of which has one of a finite, usually small, number of possible states. Cell state is determined with reference to surrounding cells some specified distance away, for example, one or two cells distant. Other cells within this surrounding area are referred to as the current cell’s neighbourhood.

Cellular automata applications to coral reef

Application of simple rules, for example, based on the number of cells in the neighbourhood with the same state, is used to determine the future state of a cell at the next iteration, or generation, of a cell.

Results from CARBOCAT model illustrate the potential of cellular automata models for generating simulated heterogeneous platform top strata and hence better understanding the origins of carbonate heterogeneities found in natural systems (from Burgess 2013).

Fuzzy logic¶

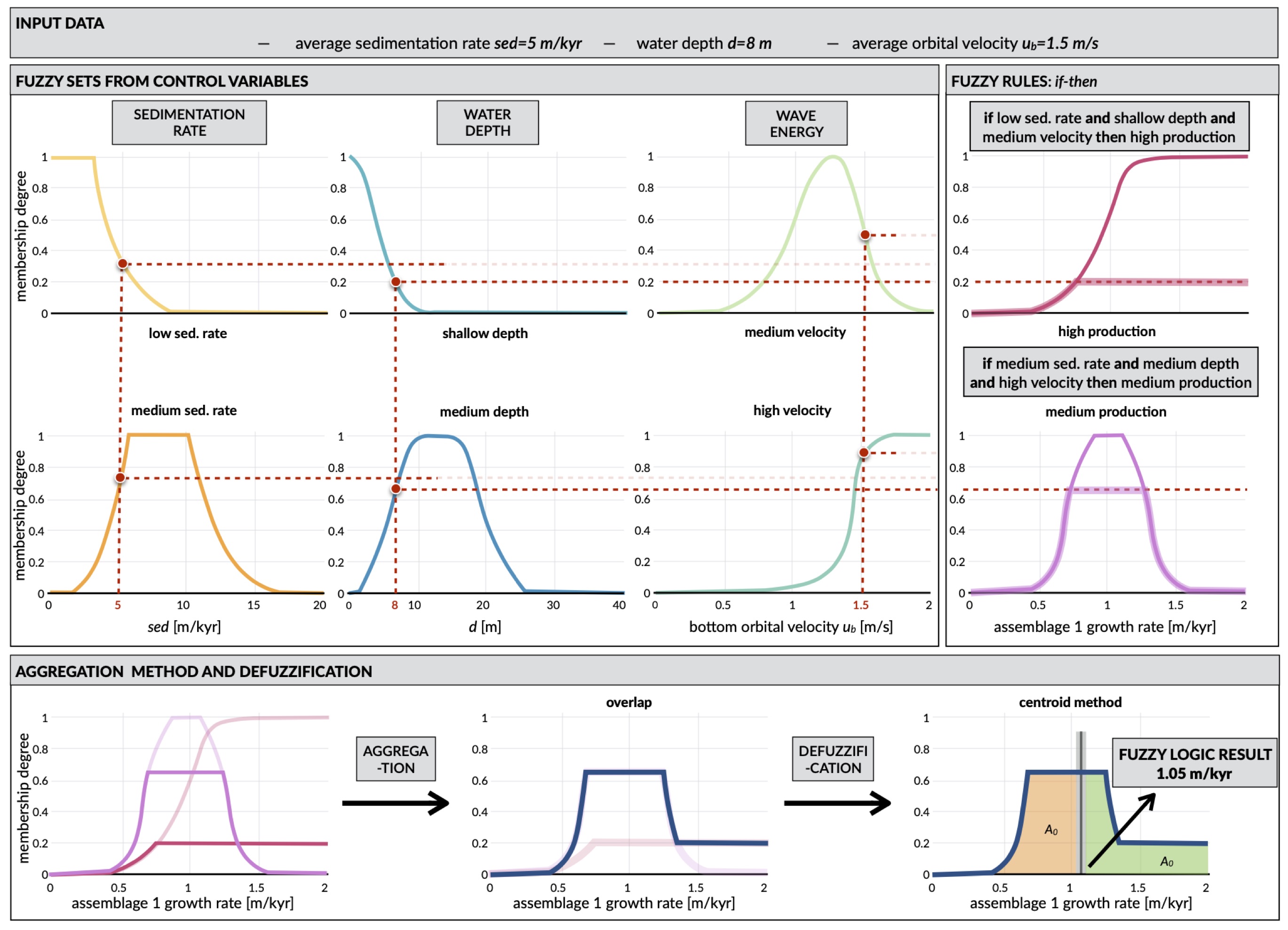

Fuzzy logic methods are able to create logical propositions from qualitative data by using linguistic logic rules and fuzzy sets. These fuzzy sets are defined with either continuous or crisp (discontinuous) boundaries.

Based on a fuzzy logic approach, carbonate system evolution can be driven entirely by a set of rules whose variables are fully adjustable. The utility and effectiveness of the approach is mostly based on the user’s understanding of the modelled carbonate system. The technique is specifically useful to estimate how particular variable, in isolation or in combination with other factors, influences carbonate depositional geometries and reef adaptation.

Fig. 29 Fuzzy logic model of carbonate reef¶

In the example of fuzzy logic set above, carbonate growth depends on three types of control variables:

depth (or accommodation space),

wave energy (derived from ocean bottom orbital velocity) and

sedimentation rate.

Note

For each of these variables, one can define a range of fuzzy sets using membership functions. A membership function is a curve showing the degree of truth (i.e. ranging between 0 and 1) of membership in a particular fuzzy set. These curves can be simple triangles, trapezoids, bell-shaped curves, or have more complicated shapes as shown above.

Production of any specific coral assemblage is then computed from a series of fuzzy rules. A fuzzy rule is a logic if-then rule defined from the fuzzy sets.

In the above algorithm, the combination of the fuzzy sets in each fuzzy rule is restricted to the and operator. The amalgamation of competing fuzzy rules is usually referred to as a fuzzy system. Summation of multiple rules from the fuzzy system by truncation of the membership functions produces a fuzzy answer in the form of a membership set. The last step consists in computing a single number for this fuzzy set through defuzzification.

Modelling GBR past evolution¶

Evolution since Last Glacial Maximum¶

Using badlands, a reduced-complexity model developed in the School of Geosciences, we compute over geological time: sediment transport from landmasses to coasts, reworking of marine sediments by longshore currents, and development of coral reef systems.

Note

The code links together the main sedimentary processes driving mixed siliciclastic-carbonate system dynamics. It offers a methodology for objective and quantitative sediment fate estimations over regional and millennial time-scales.

Examples of badlands simulation for the entire GBR.

Simulations of the Holocene evolution of the Great Barrier Reef show: (1) how high sediment loads from catchments erosion prevented coral growth during the early transgression phase and favoured sediment gravity-flows in the deepest parts of the northern region basin floor (prior to 8 ka before present (BP)); (2) how the fine balance between climate, sea-level, and margin physiography enabled coral reefs to thrive under limited shelf sedimentation rates after ~6 ka BP; and, (3) how since 3 ka BP, with the decrease of accommodation space, reduced of vertical growth led to the lateral extension of reefs consistent with available observational data.

Influence of carbonate platform on geomorphological development of the margin¶

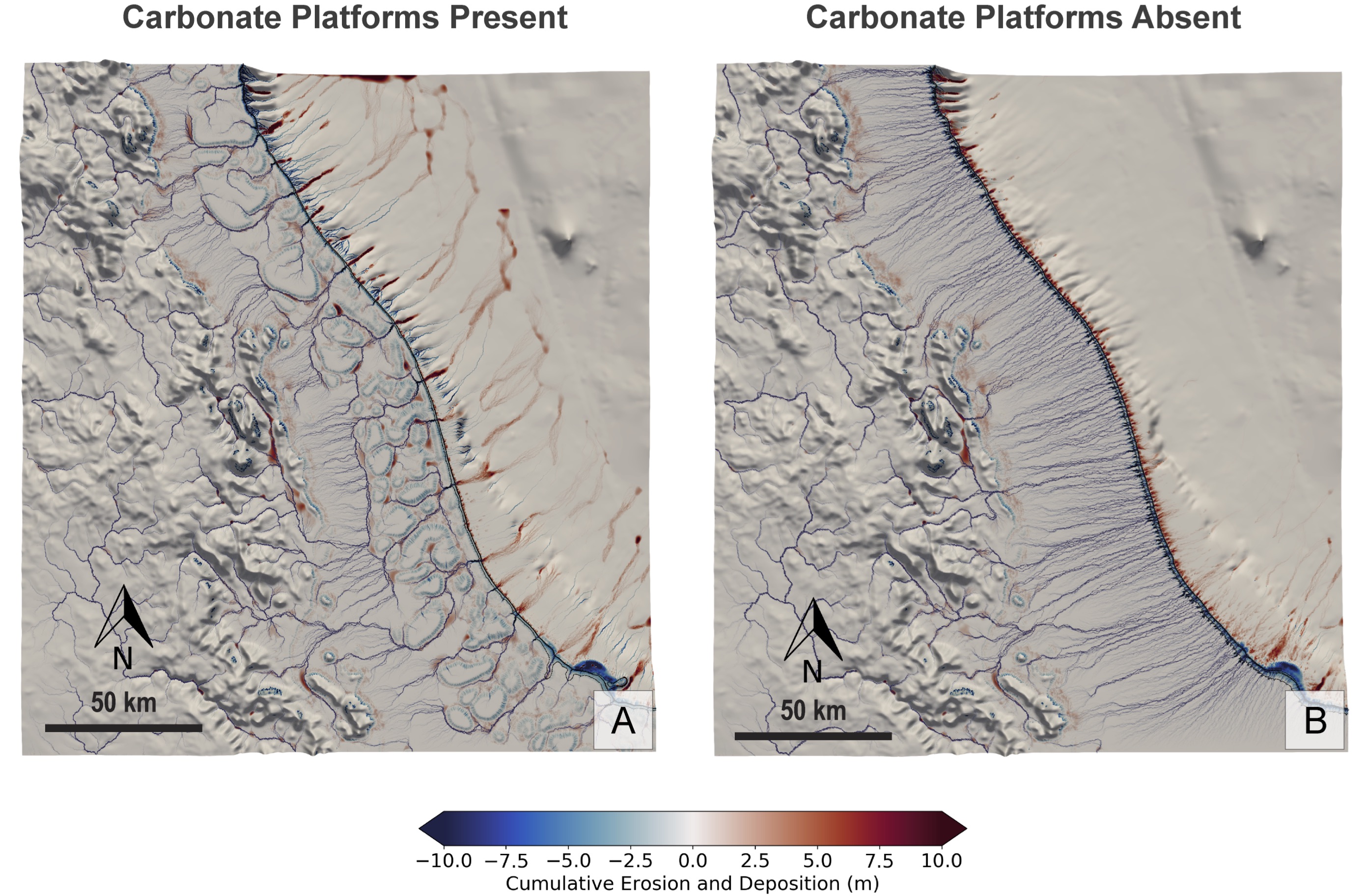

Sedimentation regimes on the Great Barrier Reef margin often do not confine to more conventional sequence stratigraphic models, presenting difficulties when attempting to identify key processes that control the margin’s geomorphological evolution.

Note

By obstructing and modifying down-shelf and down-slope flows, carbonate platforms are thought to play a central role in altering the distribution and morphological presentation of common margin features.

Using badlands, we can test the role of the carbonate platforms in reproducing several features (i.e. paleochannels, shelf-confined fluvial sediment mounds, shelf-edge deltas, canyons, and surface gravity flows) that have been described from observational data (seismic sections, multibeam bathymetry, sediment cores, and backscatter imagery).

When carbonate platforms are present in model simulations, several notable geomorphological features appear, especially during lowstand. Upon exposure of the shelf, platforms reduce stream power, promoting mounding of fluvial sediments around platforms. On the outer shelf, rivers and streams are re-routed and coalesce between platforms, depositing shelf-edge deltas and incising paleochannels through knickpoint retreat.

Fig. 30 GBR geomorphology induced by carbonate platform from Thran et al. (2020).¶

Additionally, steep platform topography triggers incision of slope canyons by hyperpycnal flows, and platforms act as conduits for the delivery of land and shelf-derived sediments to the continental slope and basin. When platforms are absent from the topographic surface, the model is unable to reproduce many of these features.

Important

Results demonstrate the essential role of carbonate platform topography in modulating key bedload processes, and therefore exert direct control on the development of various geomorphological features within the shelf, slope, and basin environments.

Hands-on examples¶

1D model of coral assemblages evolution¶

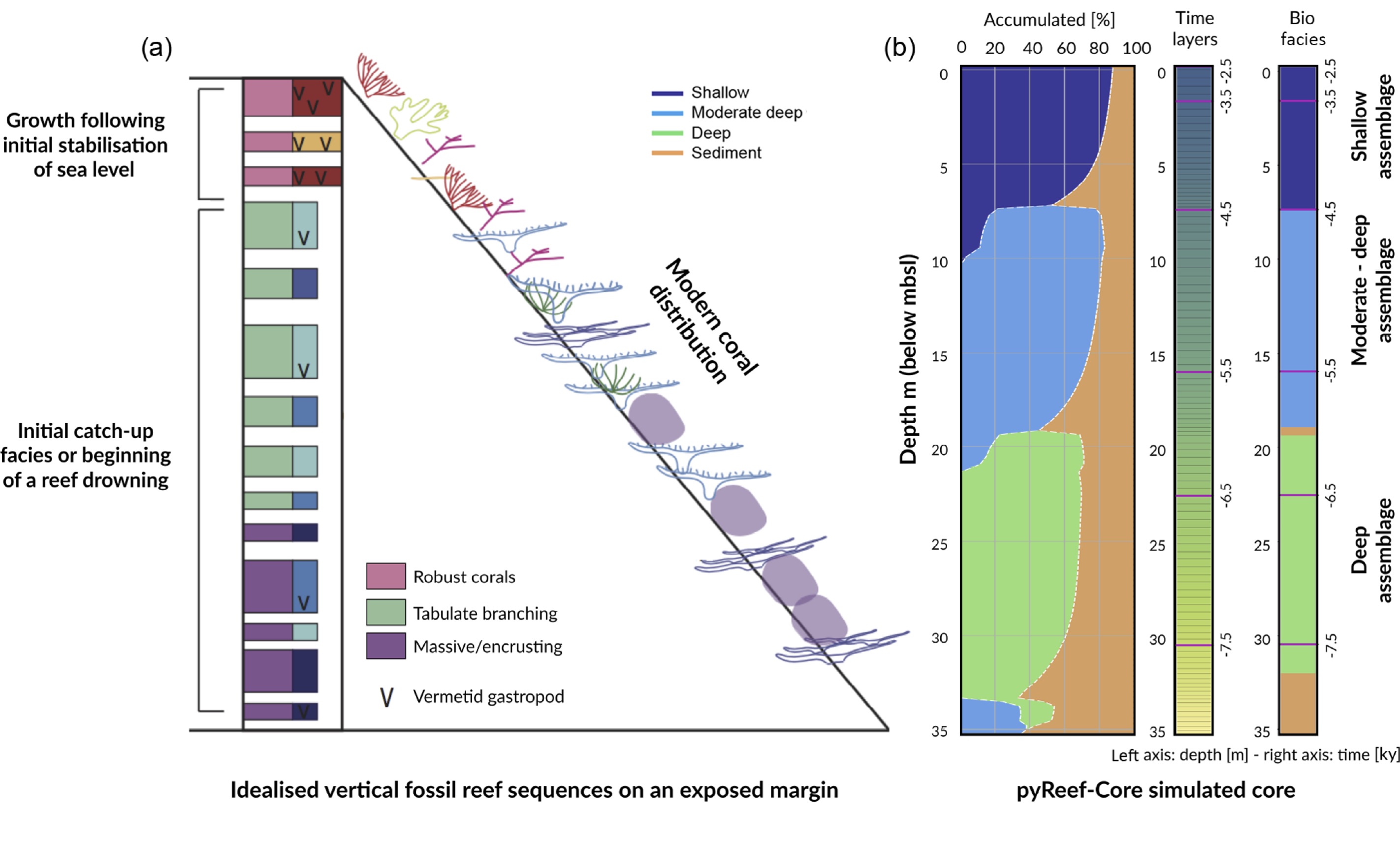

Using pyReef model, we will simulate typical sequences of coral assemblages found in the GBR based on different initial conditions.

Fig. 31 pyReef model outputs used in this exercise.¶

Use the link above to run different scenarios of coral growth with pyReef.

Carbonate platform evolution since the last LGM¶

With badlands, you will simulate the evolution of a carbonate platform over the last 10,000 years accounting for the impact of waves, sediment transport and sea-level changes.

Click on the link above to start running the simulation in a Jupyter Notebook.

Miscellaneous¶

The Game of Life¶

Conway was interested in a problem presented in the 1940s by mathematician John von Neumann, who attempted to find a hypothetical machine that could build copies of itself. The Game of Life emerged as Conway’s successful attempt to drastically simplify von Neumann’s ideas. From a theoretical point of view, it is interesting because it has the power of a universal Turing machine: that is, anything that can be computed algorithmically can be computed within Conway’s Game of Life.

Play with Conway’s Game of Life here.