Runup models¶

This notebook is from the py-wave-runup examples from Vitousek et al. (2017).

Note

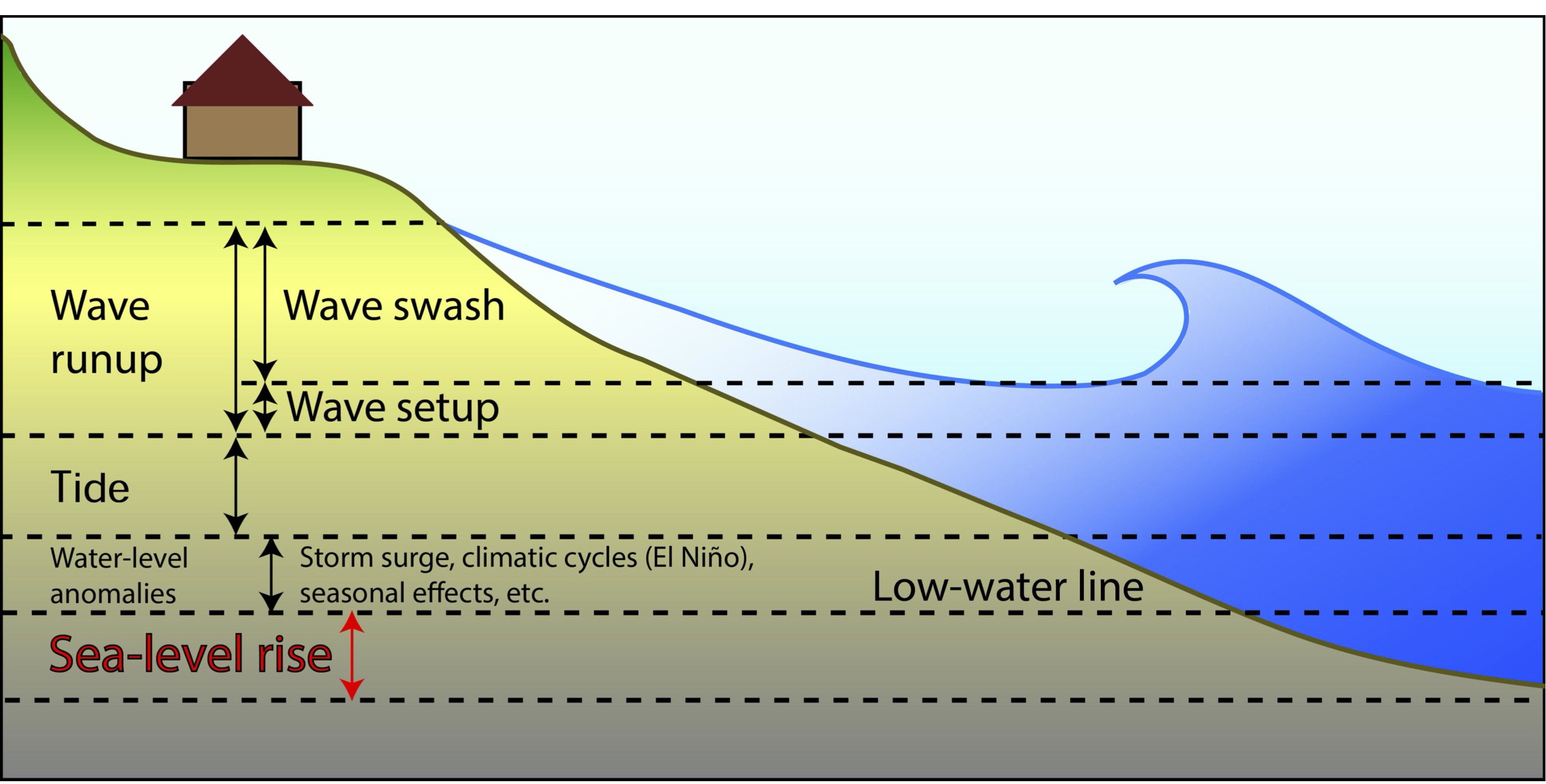

Runup is the final stage of a wave’s landward propagation, and thus the determinant of the most landward position a wave can reach before receding seaward. Runup above the local ocean level outside the surf zone results from a combination of two processes:

wave induced setup and

swash.

Fig. 18 The water-level components that contribute to coastal flooding from Vitousek et al. (2017).¶

Past research has focussed on modelling maximum wave runup values, most commonly Rmax and R2%.

Rmax is the greatest elevation obtained by a single runup event within a given time period and is therefore a function of record length.

R2% is a statistical measure of the elevation exceeded by only 2% of all runup or swash events within a time period.

In this example, we will evaluate the accuracy of the Stockdon et al (2006) runup model.

Stockdon, H. F., Holman, R. A., Howd, P. A., & Sallenger, A. H. (2006). Empirical parameterization of setup, swash, and runup. Coastal Engineering, 53(7), 573–588. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2005.12.005

To do this, we will use the compiled wave runup observations provided by Power et al (2018).

Power, H.E., Gharabaghi, B., Bonakdari, H., Robertson, B., Atkinson, A.L., Baldock, T.E., 2018. Prediction of wave runup on beaches using Gene-Expression Programming and empirical relationships. Coastal Engineering. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coastaleng.2018.10.006

The Stockdon et al (2006) wave runup model comprises of two relationships, one for dissipative beaches (i.e. \(\zeta < 0.3\)) Eqn (18):

and a seperate relationship for intermediate and reflective beaches (i.e. \(\zeta > 0.3\)):

First, let’s import our required packages:

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from sklearn.metrics import mean_squared_error, r2_score

import waverunup as ru

%matplotlib inline

Let’s import the Power et al (2018) runup data, which is included in this package.

import pandas as pd

# Manually define names for each column

names = [

"dataset",

"beach",

"case",

"lab_field",

"hs",

"tp",

"beta",

"d50",

"roughness",

"r2",

]

df = pd.read_csv('../pracenv/dataset/power18.csv', encoding="utf8", names=names, skiprows=1)

print(df.head())

dataset beach case lab_field hs tp beta d50 \

0 ATKINSON2017 AUSTINMER AU24-1 F 0.739477 6.4 0.102 0.000445

1 ATKINSON2017 AUSTINMER AU24-2 F 0.729347 6.4 0.101 0.000445

2 ATKINSON2017 AUSTINMER AU24-3 F 0.729347 6.4 0.115 0.000445

3 ATKINSON2017 AUSTINMER AU24-4 F 0.719217 6.4 0.115 0.000445

4 ATKINSON2017 AUSTINMER AU24-5 F 0.719217 6.4 0.115 0.000445

roughness r2

0 0.001112 1.979

1 0.001112 1.862

2 0.001112 1.695

3 0.001112 1.604

4 0.001112 1.515

We can see that this dataset gives us \(H_{s}\) (significant wave height), \(T_{p}\) (peak wave period), \(\tan \beta\) (beach slope). Let’s import the Stockdon runup model and calculate the estimated \(R_{2}\) runup value for each row in this dataset.

# Initalize the Stockdon 2006 model with values from the dataset

sto06 = ru.models.Stockdon2006(Hs=df.hs, Tp=df.tp, beta=df.beta)

# Append a new column at the end of our dataset with Stockdon 2006 R2 estimations

df["sto06_r2"] = sto06.R2

# Check the first few rows of observed vs. modelled R2

print(df[["r2", "sto06_r2"]].head())

r2 sto06_r2

0 1.979 0.645571

1 1.862 0.636336

2 1.695 0.704238

3 1.604 0.699330

4 1.515 0.699330

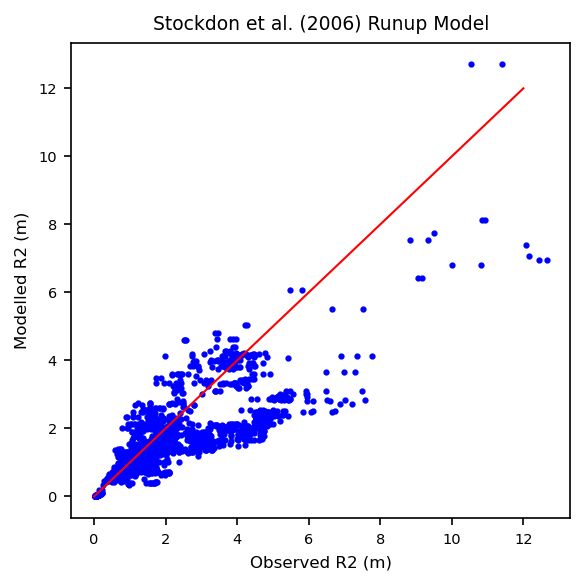

Now let’s create a plot of observed R2 values vs. predicted R2 values:

# Plot data

fig, ax1 = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(4, 4), dpi=150)

ax1.plot(df.r2, df.sto06_r2, "b.", markersize=4, linewidth=0.5)

# Add 1:1 line to indicate perfect fit

ax1.plot([0, 12], [0, 12], "r-", linewidth=1)

# Add axis labels

ax1.set_xlabel("Observed R2 (m)", fontsize=8)

ax1.set_ylabel("Modelled R2 (m)", fontsize=8)

ax1.set_title("Stockdon et al. (2006) Runup Model", fontsize=9)

plt.xticks(fontsize=7, rotation=0)

plt.yticks(fontsize=7, rotation=0)

plt.tight_layout()

We can see there is a fair amount of scatter, especially as we get larger wave runup heights. This indicates that the model might not be working as well as we might have hoped.

Let’s also check RMSE and coefficient of determination values:

print("R2 Score: {0:.2f}".format(r2_score(df.r2, df.sto06_r2)))

print("RMSE: {0:.2f} m".format(np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(df.r2, df.sto06_r2))))

R2 Score: 0.54

RMSE: 1.21 m

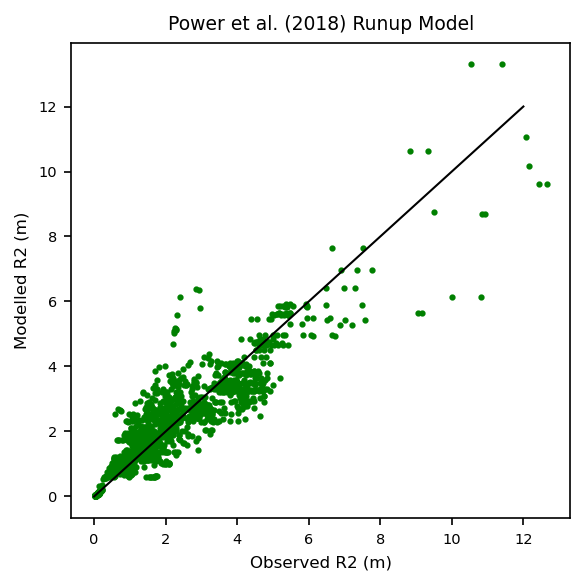

Power et al. (2018) model¶

Let us try the Power et al. (2018) model:

df = pd.read_csv('../pracenv/dataset/power18.csv', encoding="utf8", names=names, skiprows=1)

# Initalize the Nielsen 2009 model with values from the dataset

pow18 = ru.models.Power2018(Hs=df.hs, Tp=df.tp, beta=df.beta, r=df.roughness)

# Append a new column at the end of our dataset with Stockdon 2006 R2 estimations

df["pow18_r2"] = pow18.R2

# Check the first few rows of observed vs. modelled R2

print(df[["r2", "pow18_r2"]].head())

r2 pow18_r2

0 1.979 1.034144

1 1.862 1.015685

2 1.695 1.127796

3 1.604 1.115673

4 1.515 1.115673

# Plot data

fig, ax1 = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(4, 4), dpi=150)

ax1.plot(df.r2, df.pow18_r2, "g.", markersize=4, linewidth=0.5)

# Add 1:1 line to indicate perfect fit

ax1.plot([0, 12], [0, 12], "k-", linewidth=1)

# Add axis labels

ax1.set_xlabel("Observed R2 (m)", fontsize=8)

ax1.set_ylabel("Modelled R2 (m)", fontsize=8)

ax1.set_title("Power et al. (2018) Runup Model", fontsize=9)

plt.xticks(fontsize=7, rotation=0)

plt.yticks(fontsize=7, rotation=0)

plt.tight_layout()

print("R2 Score: {0:.2f}".format(r2_score(df.r2, df.pow18_r2)))

print("RMSE: {0:.2f} m".format(np.sqrt(mean_squared_error(df.r2, df.pow18_r2))))

R2 Score: 0.82

RMSE: 0.75 m